Father Richard Veras

In his book, The Psalms, Monsignor Luigi Giussani writes: "Prayer does not ask for something we want, something we have thought of, prayer asks of someone Other, because of the impression this Other makes upon us."

Begging for a Presence

Christian prayer is not about me. It is not about my ability to concentrate or how peaceful I can feel. Christian prayer is begging for the Presence of God. Not God in general, however, but God who reveals himself in Jesus Christ and through the community of the Church makes an impression on me by touching my life in particular ways.

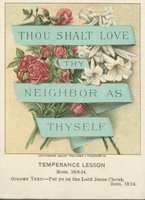

For the Jews and Christians memory is an indispensable aspect of prayer. The prayers of the Jewish people always recall the saving actions of God. When offering the first fruits of their harvest they would say, "My father was a wandering Aramean......[God] brought us out of Egypt with his strong hand and outstretched arm" (Dt 26:5, 8). Notice that the prayer is not concerned with what my father is, but rather with the outstretched arm that saves us. It is what God does, regardless of our personal worthiness, that saves us. Prayer is an acknowledgement, full of affection and entreaty, of his saving Presence.

Memory and experience

At the Mass we call to memory the saving actions of Jesus Christ. The focus of the Mass is not the attentiveness of the congregation or even the priest; the Mass is centered around the Presence of Christ. If I find myself distracted during Mass, does that stop Christ from coming? No! When I wake up from distraction it is a moment to thank Jesus again for his Presence. If instead I concentrate on how inattentive I am, I simply extend the distraction. The same goes for the rosary (another prayer full of memory) and every other prayer.

But even salvation history itself does not awaken me unless I can also locate the Presence of Christ in my personal experience. To awaken the familiarity with the One to whom I pray, I must recall the particular ways he has saved me. I tell engaged couples that the love for their fiance that they discovered in themselves, and the way that their fiance's love has awakened them, are the very love of Christ. If they have experienced true love then they have experienced Jesus, they have met him. Thus, when they pray, they now know to whom they are praying; they have become familiar with the Presence for and to whom they are begging.

Saint Therese of Lisieux said that for years she slept through prayers in the convent, but that this did not bother her because parents love their children as much when they are asleep as when they are awake. She understood that her own parents' love for her was the very love of God the Father in her life, and that God could not love her less than her parents. So she does not look at her weakness, but rejoices in the fatherly Presence of God. Her prayer was a response of God's presence in her life. She had experienced the attractiveness of his Presence, and so begging him continually for more was the most human response.

The need for the Church

The Psalms themselves are the prayers of the Jewish people after God has entered into their history. I encounter God, my desire is awakened, and I beg for his Presence more and more, as the lover wants to see the beloved as much as possible, and as the child continually looks for the loving and affirming presence of his mother and father.

God's love for me becomes this concrete only in the community of the Church, through those members of the Church that Christ places closest to me. This is why the most exalted prayer is always the liturgy, the prayer of the Church, the prayer arising from the unity of the people where God's Presence mysteriously abides.

Guissani writes in The Psalms, "We are at the weakest point in our behavior when we begin with ourselves, so the greatness of man is in living close to God, as a young man near his parents."

Christian prayer in the Church can be this simple.

Magnificat January 2006, Vol 7, No. 12